Classic Car Magazine article

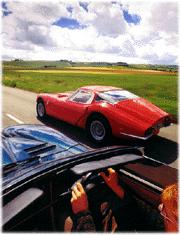

Family ties

Marcos has never built a car more beautiful than the 1800, but the old influences are creeping back

Three decades of fluctuating company fortunes and fickle automotive fashions separate these two Marcos sports cars and yet, incredibly, they remain remarkably alike.Consider the driver's environment. In both models he is slung back in an all enveloping hammock - style seat in which his entire frame is positioned almost parallel with the tarmac. The seat is not adjustable, but the pedals and the steering wheel are. Reclining in the thirty - something Marcos 1800, designed by Dennis Adams (of Lister fame) and powered by Volvo's pushrod P1800 engine, the pedals can be dialled forward and backwards by twisting a large black knob below the steering wheel. The wheel itself is adjusted under the bonnet at the steering column.

Fast forward three decades to the 1996 Marcos LM500 designed by Dennis Adams' nephew Leigh (at least in part, more on that later) and powered by Rover's potent overhead valve V8. The driving environment remains almost unchanged. Only difference this time is that a neat little button under the dash whirs the pedals fore and aft. Similarly, the flick of a lever on the steering column will free the steering wheel to suit your personal dimensions. Technology's the thing; an increase in the user-friendliness of the automobile. The rest is business as usual: pure machismo, pure muscle, pure Marcos.

Then consider the view through the front windscreen: muscular wings and swollen wheel arches, narrow vents through which the engine can breathe and a glassfibre bonnet that visibly shudders on reaching the nadir of yump-engraved roads. And that's just the 1800. The LM500 goes further still, with vast swathes of glassfibre carved out of the nose in search of greater downforce, greater airflow, greater visual impact.

Nothing quite matches the 1800 for sheer driving thrills. From the moment the door is slammed shut and your body has shimmied into a comfortable position-and your feet have disappeared down the darkened corridor that is the footwell-your attention is unwavering. On ignition, the bonnet shrieks at the cabin and the cabin bellows back and you, the hapless driver, have no choice but to slide open the side window and search for aural security in more familiar surroundings, such as the motorway traffic flashing past. Then you realise how low you are; how big those 20-tonne artics look.

Then there is driving the thing. A Marcos calls upon all your senses, beginning with a sizeable chunk of first-night nerves that are gradually and gratefully eroded as the boundaries are explored and the engine given freedom to roam.

The four-speed (with overdrive) P1800 gearbox is ideal for a sporting drive, something which owners of the similarly equipped Volvo B18 knew a little about but no-one else had guessed was possible. The choice of Volvo equipment rings like true Marcos ingenuity, bucking the trend once again. In reality, says Jem Marsh, 'it was the only engine we could find which would fit'.

Production of the Volvo-powered 1800 was discontinued after just 106 models and two years; the expensive Swedish unit being forsaken in favour of cheaper Ford power. Nevertheless, those early models with independent suspension and flexible, unstressed Volvo power remain the most popular by far.

The twin-Webered unit truly comes into its own above 3,000rpm: the exhaust note bounces sonorously off the hedgerows, raising its game from burbling traffic miser to open-road reveller loaded with mid-range torque. There is an urgency about everything; the sense that, no matter what the conditions, it would be sacrilege to lift your throttle foot. This is true of both models-old and new. Bookies would call it pedigree.

On the road

We took both cars on a nostalgic journey to some old Marcos stomping grounds, beginning at Kingston upon Thames, Surrey and finishing at the present factory in Westbury, Wiltshire. An old wooden and corrugated shed by the Thames in Kingston was the temporary home to Marcos for several months of head-scratching in 1962. In fact, the site was little more than a roof over their heads while company founder Jem Marsh closed his Monocoque Body Chassis Company (which had built the giant-killing Frank Costin/Dennis Adams-designed Marcos Gullwing) and formed Marcos Cars Ltd.

Our single stop before Westbury was at Greenland Mills, in nearby Bradford-on-Avon. A former woollen mill and once upon a time the home of Royal Enfield motorcycles, Greenland Mills was the riverside base from which the design innovations of brothers Dennis and Peter Adams sprang from the winter of 1962 until they left Marcos to set up independently in 1965. Marcos was there until 1971. At its peak, there were 120 employees at the mill; in the early days, Jem ran the business while Dennis and Peter built the cars and trained the workers in the art of wooden chassis-a Marcos hallmark until 1968-and glassfibre construction.

Ironically, the 1800 was originally intended as no more than a stopgap model to boost sales of the Fastback; something to exhibit at the 1964 Racing Car Show. As it turned out, Dennis Adams' sleek design, laid on a de Dion rear end (shelved after 32 models to cut costs) and nimble Herald/Spitfire-based front suspension and steering, proved so successful that the essential body shape has survived for more than 30 years and remains the inspiration for today's range of sports cars.

And anyone can drive it. Although this machine stands just 3ft 6.5in in height, four inches lower than the E-type, the 1800 can accommodate drivers of all sizes thanks to its deep footwells, adjustable pedals and-for the vertically challenged-the option of a dummy seat that was fondly known as 'the tadpole'.

Adams attributed his styling cues to the low front and high tails of sporting gems such as the Lister Jaguar and Renault Alpine. The 'breadvan' tail, rear lip and sculpted rear wheelarches give the 1800 its air of aggression and basic sporting instinct; the high tail warding off potential Marcos-bashers with arrogance and self-confidence. From the front the Marcos is a lesson in the art of automotive seduction. The elegant sharknose, fared-in headlights, thin steel bumpers and steeply raked windscreen offer subtlety and purity of line. There is an honesty and simplicity about the Adams design that the company has struggled to emulate since.

Interior

The impressively sculpted facia is entirely due to Adams' hatred of flat wooden dashboards, and owes plenty to the jet age and the changing depths of American concept cars. Sunk deep into the driving seat, braced between the gearbox tunnel and the door, the overriding impression is more WWII fighter than sports car. Four simple Smiths gauges grace the top of the centre console and two vertical rows of toggle switches fall away below. The principal gauges, the speedo and tachometer, sit side by side directly behind the wood-rim-and-chrome, two-spoke wheel. The view is ideal, but what is more absorbing is the way these gauges sprout from the bulkhead with no dash panel to tidy them up. The entire cabin is like this: from the sliding windows to the absence of an ashtray (when Jem Marsh gave up smoking, he felt that his customers should do the same-and would charge£150 extra if they wanted one), creature comforts were not high on the Marcos agenda.Which goes some way to explaining the somewhat inclement press today's modern car tends to receive. It's an argument that has dogged the company for several years now: why spend as much as £45,000 on a new Marcos LM500 when you can spend ten grand less on the equivalent TVR Griffith 500 and still get the same performance? Autocar summed it up succinctly in its 1995 road test of the LM500 which had, importantly, an older body style to the car featured here. It said: 'The Marcos is undoubtedly more exclusive but rarity alone cannot make up the difference.'

What a difference a year makes. Two appearances at Le Mans (a finish in 1995; retirement while leading class in 1996), a revised body style and a new dashboard design are three elements that are spearheading the Marcos revival in the second half of the Nineties. Orders are expected to reach 100 cars by the New Year.

The changes are small yet crucial and most are down to Peter Adams' son Leigh who, barely two years out of university, is level-bent on steering the LM's metamorphosis along the right track. He is also the first-ever design graduate to work at Marcos.

The early signs are good. The hard edges are being honed away in favour of more sweeping curves and subtle lines. The doors, the bonnet edges and the rear lip have all been softened in an effort to bring the screaming dinosaur into the 21st century; not forgetting that, in these days of retro-roadsters, designing for the future tends to include more than a cursory glance at the past. The front air dam holds a clue. It still clings greedily to the tarmac, but the indicators have been moved back within the air ducts-just like the 1800. And there is more to come, we are assured, although we must hold our breath until the next Motor Show.

So is Marcos up to its old tricks again? Rushing to produce a new body in time for a high-profile motor show that will boost sales and bring in the bucks? Considering that the 1800 was the result of just such an eleventh hour drive back in 1964, I hope so.